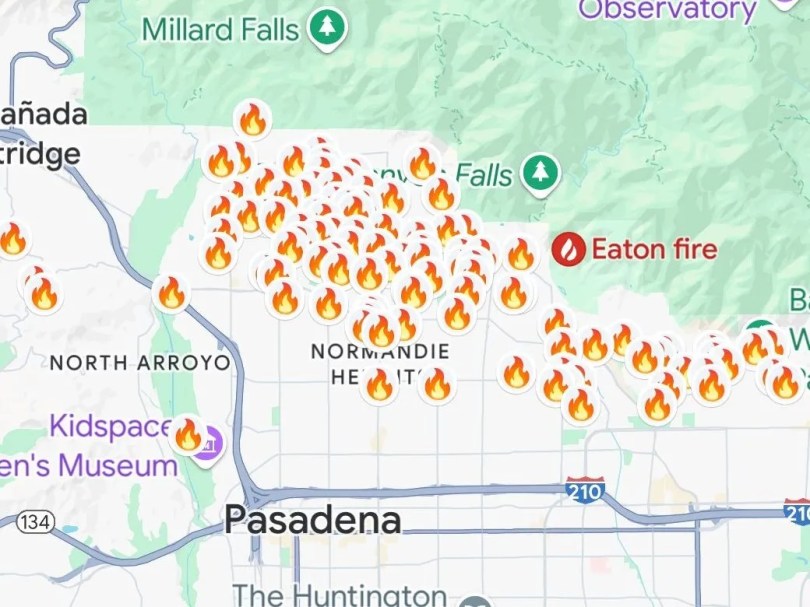

Rebuilding from the Eaton Fire is a full-time job. But it also makes my actual full-time job, writing about disinformation and conspiracy theories, nearly impossible. Your Patreon subscriptions help me carve out the time to write and research, so I can stay ahead of the madness while I deal with the madness. Thank you!

It’s been a year since we lost our home and our neighborhood in the Eaton Fire. What began as desperate hours become a few days of panicked flight, which turned into weeks of slow-rolling horror as the new reality settled in. Then it became months of exhausting struggle, endless frustration, gallows humor, tree-destroying notetaking and list-making, and a seemingly never-ending supply of walls to bang our heads into.

And that’s just been our experience with our mortgage company.

Every survivor of the Eaton and Palisades Fires has that one company or entity that’s made their post-disaster life a bureaucratic hellscape. For many, it’s been their insurance company holding up rebuilding payments or refusing loss of use money with demands to move back into an unlivable house. For others, it’s been a contractor suddenly not showing up. Or FEMA not paying out a grant. Or the city of LA dragging its feet on permits or making unreasonable planning demands about drainage other some other dumb crap.

One thing you’ll find with survivors is that we all have different nightmares, but we all have nightmares.

Ours is our mortgage company. If anything symbolizes our year of struggle and strife, of uncertainty and frustration, it’s been our multi-front war with the massive corporation that holds the note on our no longer extant house. Rather than go into the litany of battles we’ve fought this year, I want to explore this one particular battle. It symbolizes with ruthless efficiency not just how difficult rebuilding is, but how soul-sucking and dispiriting it is to be an American in search of answers and help from a major corporation, and to get nothing back but busy work and delays delivered with perky hold music.

Writing about our struggle as homeowners does not invalidate the experience of renters, who are going through their own horrific battles against landlords and property managers. Being able to own any kind of home in LA is a privilege I don’t take lightly. But as much as a privilege as it is, you’ll forgive me if I’ve come to think of it more as a millstone – or maybe an empty string that once held a millstone, but which still weighs a ton. Metaphors fail me.

Please also note that this is not a comprehensive listing of every contact we’ve had with the mortgage company, but a summary of the madness of the last year. I’ve spared you all every single detail, because many are too boring or stupid to recount. Or they’re lost in the haze.

One of the first things we had to do when we lost the house was figure out if we had to actually pay the mortgage. Do you still send in payments on a home that doesn’t exist anymore? As it turns out, you do. The bank is not going to let you off the hook that easy. But they will work with you, because ultimately, they’d rather have your money than have you default.

So we went into forbearance with our mortgage company, which I’m calling Bob, because I don’t want to publicly light up a company we’re still doing business with. Despite our ordeal, we still need to work with them, and to do that, some details have to be held a little closer than I might like.

Bob wasn’t the first company to hold our mortgage, ending up as its administrator after it bought or absorbed or consolidated with some other mortgage company. But Bob is our current mortgage holder. So we called Bob a few days after the fire to talk about what we could do while we figure out what to do.

Bob, or one of the many people who work for Bob, told us we could put our payments on pause for a year in order to save money and simplify our financial life as we tended to other matters. Ultimately, of course, we would have to decide how to make up those payments. There were three options we could pick: a balloon payment in a year, tacking the payment on to the very end of the loan, or a loan modification that restructured the entire loan with the same interest rate.

But that was a problem for down the road, we thought. In the first few months after the fire, we had to figure out much more basic and elemental things. So forbearance it was.

Oh, and would we keep accumulating interest on our unmade payments, thereby actually increasing the amount of money we’d owe Bob over the life of the loan?

After about six or so months, it was time to decide if we wanted to start making the payments again, and how. We’d been getting letters the entire year that we were past due on our mortgage, but Bob told us that they were just form letters sent automatically by their system, and that they could be ignored. Could Bob just not send them? Of course not, but they didn’t matter. We were squarely in forbearance. And we knew from our earlier conversations with Bob that we’d be able to do the loan modification, so there was nothing to worry about. As planned, we called in October to set it up. We were told we could essentially modify our loan to a 40 year term starting now, and keep our low interest rate – thank you to COVID for that one. So we waited. And we waited. And heard nothing.

We called Bob again, and spoke to someone completely different (which we’d done every time we’d called). After again explaining what we’d been told, we were kicked to a different department, and were told that Bob doesn’t do loan modifications without an application – though we’d been told earlier we didn’t need to fill out anything to apply for one, because the government had declared the fire as a disaster. Then we called again, spoke to someone new again, got kicked around again, this time to something called “loss mitigation,” and were told that Bob doesn’t do loan modifications AT ALL, and we weren’t eligible for one anyway because there’s no home to collateralize against the loan.

Got that? No, you don’t.

Since that call completely contradicted everything we’d been told, we called again. We again spoke to someone different in a different department, who told us we are eligible, and don’t need to apply, but need to get approval from Fannie Mae as the actual funder of the loan – and that Bob would call us when they had it. So again, different people tell us different things that contradict each other. But at least someone would call us this time.

So did they call us? They did not. We called again. And again talked to someone new. And explained it all again. The trauma, the loss, the uncertainty. Then that person told us that Fannie Mae doesn’t make loan modification approvals on a property that doesn’t have a home. While at the same time, our forbearance had been extended in anticipation of us getting a loan modification, because we need to be in forbearance to get the loan modification.

Which they don’t do. Except when they do?

We called again. Swimming in contradictory information and demands, we went through our whole sad story. Again. Then we essentially begged a call center employee to speak to someone in management after this person told us flat out, in a charming southern drawl, “I don’t know what to do with you.” Again, this is their “loss mitigation” department, which apparently does not know how to handle loss mitigation. Ultimately, we were connected to a VP. This VP is now personally handling our case. Except it’s not being handled, because we are still getting letters from Bob telling us that we are not only delinquent in our payments, we are in default. And we get these letters at the exact same time we get letters telling us we have gotten another three months on our forbearance.

Finally, this VP told us that we have to get the default letters as a matter of federal law, even though we are not in default. I don’t know what kind of madness it is to tell people they are in default despite not being in default, and to not tell people that the letters telling them they’re in default can be discarded. But that’s Bob for you. Or maybe it’s the system that keeps Bob and his brothers fat and satisfied on our interest payments.

It should not have to take a senior manager, dozens of letters, and entire reams of paper to tell us that we are where we thought we were. Nor should it have taken us entire days spent on the phone with a dozen or more people in four different departments, none of whom were able to tell us anything consistent until we threw ourselves down and begged. It should not be like this. But none of this should be like it is.

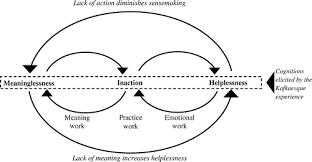

If this Kafkaesque nightmare was our only interaction with Bob, maybe that would take some of the sting out of our relationship’s disarray.

But it’s not by a longshot. Bob has several more attack surfaces on which to bombard us with nonsense, and I’m going to go into them here, because they are insane.

One of these is homeowners insurance. Did you know that you don’t actually need to insure a home that doesn’t exist? We didn’t, until our insurance company (who we like a lot) called us to help us cancel ours because they don’t insure land. We’d be able to buy more when we had a new home, but until then, we could just pay renters insurance on where we’re living. Sounds great! Winning!

Then came Bob. Bob sent us a letter telling us they had been informed we had cancelled our homeowners insurance, and that despite having no home to insure, we had to have homeowners insurance because our home is “vacant/abandoned.” So they would be buying us something called Lender Purchased Insurance unless we prove the land itself is vacant. And naturally, LPI is more expensive than what we had before and we’d have no choice on who they bought it from. But we didn’t need a choice, because we didn’t need it at all. There was nothing to insure.

So we sent proof in the form of our Army Corps of Engineers confirmation that our land was cleared and there is no home to be “vacant/abandoned.” After sending this proof, we were again told we needed to send proof. Then we sent proof again, and were told the LPI was being canceled. Except we then got another call asking for more documentation, even though the person calling us was able to see in our file that the LPI was canceled and said so!

This is another “feature” of Bob. The people who call us don’t appear to have read our file, and the people we talk to when we call don’t appear to be able to read other departments’ files. So by design, or by dint of incompetence, nobody at Bob has any idea what anyone else at Bob has done. We get conflicting calls and letters from different departments. We get conflicting calls and letters from the same department. We get them on the same day.

Then there’s the escrow debacle, proving not only that these companies don’t work in the best interests of their customers, but that they don’t seem to understand or feel like they have to follow the laws that govern the rest of us.

When your house burns down and you file an insurance claim, you get back a Very Large Check from your insurance company to rebuild or repair your dwelling. Except this Very Large Check isn’t made out to you. It’s made out to you and your mortgage holder. You just get it first, sign it, and send it via certified mail to the mortgage holder. They sign it and deposit it in an escrow account, making payments to you when you hit certain milestones in your rebuilding.

“Wait, this means your money isn’t actually yours?” you ask? That’s exactly what it means, because the mortgage company holds your debt. But they’re nice enough to manage it for you, at least. Right?

We were fortunate enough to have an overage between what we still owe and what the Very Large Check was made out for. Bob told us that the overage was our money, that they had no right to it, and that they’d send it to us right away. The rest of the money would be paid out when we made progress on the new house, such as sending in a materials list and blueprints. Even though we were months away from any such documents, at least we’d get the overage and could keep it under our control, right?

Clearly not. Instead, we had to fight Bob every step of the way to get our money, which they told us was not their money. After multiple calls (with the usual explanations every time of what we were going through,) Bob flat out told us that they’d release the money, but they were making an “exception” and had to go through multiple legal steps to release the funds. After months and numerous calls, they were nice enough to send us our overage, after making sure we knew what a wonderful and outsized thing they were doing for us.

We fought the battle again a few months later, trying to get a release of funds after we’d sent in our plans. We didn’t get 1/3 of what was left, which is what we’d been told we’d get, but one third of the total amount of the Very Large Check minus the overage that we’d already gotten. Building a home in LA is really expensive, and we needed what we needed when we were supposed to get it. When we called Bob (naturally speaking to someone new) they told us that Bob never releases a third of what’s left after the overage. And an exception would have to be made.

Again, two people telling us totally different things that totally contradict each other. And we have to jump through hoops inside hoops to get any kind of satisfaction, costing us hours of time and unmeasurable anguish.

But hey, at least that Very Large Check is earning some sweet interest in Bob’s escrow account, right? You bet it is, after California passed a bill requiring insurers to pay 2% interest to the homeowner on insurance payouts. A little help for us fire survivors, right?

Nah. Bob couldn’t tell us what kind of interest the money was making, how much it had made, when we’d get it, or where we could see it. When pressed, Bob told us that “things are handled on a case by case basis.” Which is not actually how law works. There is no law that says white-bordered stop signs are optional after 9pm, nor is there a law that mortgage companies can follow if they feel like paying escrow, but only on a case by case basis.

We have deployed every weapon in our limited arsenal to fight back against Bob. We’ve asked for a case manager to be assigned. They don’t do that. We asked to be conferenced in to calls with multiple departments at once, so we could all be on the same page. They don’t do that. We have filed several complaints with state offices, only to have those complaints be sent to different offices, and then be told by Bob that our complaints had been resolved, despite them not being resolved in any way.

We have taken so many notes that we had to buy more notepads. Recently we were called by a client advocacy officer to tell us a new complaint had been opened up based on a very long email we sent where we included the CEO of Bob, because why not. When we asked the client advocate what the status of the complaint was, he said he had no update. When we asked if he’d called us to update us that he had no update, he said yes and sounded annoyed we’d asked the question.

Bob has us in his grasp. We can’t pay off our mortgage and also build a new house. Psychologically, we don’t want to pay a mortgage on a lost home, but we want to work with Bob to figure out a way to eventually pay what we owe on a new home. Bob tells us that customers are their top priority, but Bob’s top priority appears to be nothing more than confusing and traumatizing us. The people at Bob are mostly nice, many express genuine condolence on our loss. It’s just that they don’t know how to help, and don’t seem to have any system in place that would let them.

Meanwhile, our trauma is unearthed time and time again. A year of loss and uncertainty is packed into every call, every frustrated question, every demand to speak to a supervisor. Bob tells us they want to help, and does nothing to help. And we start over every time.

If I’ve learned anything this last year, it’s that corporations have so much power over us that they don’t need to do anything to solve the problems they’ve created. They have so much money and sway that all they know how to do is increase their money and sway. All we want is a house to call our own, but that’s not in Bob’s plan for us. These monoliths of commerce are dehumanizing centers of confusion and delay, where speaking to a person is akin to swimming up a waterfall and where getting results is like pushing a boulder up a hill while being chased by wolves who bombard you with conflicting letters.

Through it all, we are not okay. Nobody in Altadena or the Palisades is okay. We are exhausted. We are demoralized. We are just fucking tired of everything being so hard.

But we go on. Even though we can’t go on, we go on. And we go on because of people, not companies. Our community has been our saving grace. Our friends have been our lifeline. Our neighbors have been our safe havens. Our family has been our resting place. We are still here because of that. And only because of that.

Not Bob, though. Bob can sit on a tack.

You must be logged in to post a comment.