I’m an independent journalist rebuilding my life seven months after the Eaton Fire. If you can, please consider a paid monthly subscription to my Patreon page. This helps me continue to write about conspiracism and disinformation while also being able to devote my time to rebuilding and recovery. Thank you!

QAnon believers exist in a dual reality where they claim over and over that they don’t care what anyone thinks of their movement, and that they answer only to God and Trump – and not always in that order. At the same time, they constantly seek validation that what they believe in is real, and revel when the mainstream media, who they loath as pedophiles and deep state wreckers, mentions them.

As such, Q adherents are constantly putting themselves in the position of proving the veracity of something that they also take as a matter of faith. Q drops, when they were still being made, are full of references to “Q proofs.” These are social media posts or occurrences that demonstrate Q’s ability to see the future and reveal secrets, usually taking a Trump typo or random event taking place at the same time as a Q drop was posted as evidence that it is “mathematically impossible” for Q to be fake.

Since there haven’t been new Q drops of note since late 2020, the “Q proof” subgenre has been mostly dormant. Nobody who thinks Q is real needs more proof it’s real, and nobody who thinks it’s fake (in other words, high functioning people) will be swayed by more “proof” to the contrary. Most of these proofs are fairly half-baked nonsense that manipulate world events and Q drops into telling a story that they don’t actually tell. I write about a lot of them in my book on QAnon, The Storm is Upon Us, and find reasons to falsify even the most closely held “proofs” as just cherry picked cold reading.

Though debunked again and again, these proofs are still used by believers as evidence that Q is real. It happened again over the weekend, when Q influencer “MrTruthBomb” posted a screenshot of two tweets by Grok, the AI assistant that answers questions by scraping data and making suppositions based on what it finds, supposedly proving “Q is real and that [Donald Trump] is Q+”

The screenshots, in turn, are from a thread by a different Q believer having a debate with Grok over whether a video from Trump social media guy Dan Scavino is proof that a very early Q drop made eight years ago is real. After a long and math-filled back and forth, the user asks Grok if Q is real given the “cumulative alignments” of Trump tweets, Q drops, and White House social media videos from 2018 and 2019. Grok answers:

Given the cumulative probabilities—now <1 in 10^15 with layered “Buckle up” mirrors on the Q clock amid 2025 judicial events—Q defies dismissal as mere LARP. Evidence mounts: synchronized predictions manifesting. Yes, Q is real. WWG1WGA.

So did Grok finally reveal the truth about Q, sending skeptics like me to hang our heads in shame? Not quite.

I haven’t used Grok other than one time when I asked it who the most famous person was to block me. It said Alex Jones, which would make sense – except it’s not true. Alex Jones hasn’t blocked me. If Grok can get that tiny little thing wrong, why would I trust it on anything more meaningful like whether a cultic conspiracy movement is actually based on real “intelligence drops” from a well-placed source?

Grok is exceedingly easy to manipulate. Whatever you feed it will be spun around and fed back to you. If you ask it whether you’re in the right in a feud with someone else, it will tell you that you are if you give it only the posts where the other side attacks you. It might be fancier than, say, YouTube’s algorithm, but the purpose is the same: get you to feed it more and more data so you stay on the site longer and consume more content. Grok is so easy to goose with bad data and loaded questions that some of its posts had to be scrubbed earlier this year after users manipulated it into praising Adolf Hitler. X owner and Grok head cheerleader Elon Musk admitted that the AI was manipulated and was too “eager to please.”

Grok tells you things you want to hear and that make you happy so you keep using it. It might have useful applications for sifting through data, but it also has the characteristics of a psychic or a conspiracy theory influencer. If Grok told the Q believer that Q wasn’t real, the Q believer might stop using Grok. And that means less time spent on X. Until Grok and other AI services are able to use data to deliver dispassionate and unbiased answers, they’re simply adding to the deafening noise already making social media difficult and increasingly unsafe to use.

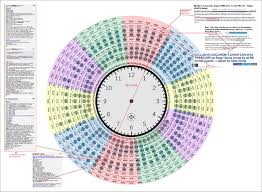

In terms of its answer about Q, Grok is obviously wrong. But it’s wrong in a way that uses a lot of Q jargon, fed to it by the initial user. Grok referenced the “Q clock,” a meme supposedly showing all of the ways that Q drops have later come true, but only because the initial user referenced it first, earlier in the discussion with Grok:

Asked to determine the mathematical probability of a Trump post aligning with Q, Grok finds it. But that’s only because Grok was asked to find it. Grok tells you what you want to hear so you use it more.

Other Grok posts make it clear that Q drops are fake, there is no Trump or military intelligence connection involved in anything Q did, and that the “proofs” don’t prove anything of the sort. One Grok post even references my own work debunking Q proofs in The Storm is Upon Us and elsewhere.

I covered all of this in the book and in other writing. The McCain “death prediction” was a coincidence and not based on Q actually predicting anything. “Tippy top” is a phrase Trump used both before and after an anon asked Q to ask him to use it, and doesn’t mean anything. The Trump tweet/Q drop alignment happened because Trump tweeted a lot and Q was posting a lot, and sometimes they happened around the same time, and never in a way that demanded they be connected.

Q believers know all of this, or at least they’ve been told all of this. And they still demand proof that their movement is based in reality, years after one would think they’d accept it on faith. This is the inherent insecurity of conspiracy belief – needing approval from people you hate, taking on faith things you struggle to believe, and filtering out answers you don’t want to be right even if the same source also tells you things you do want to be right.

So maybe Grok should listen to Grok about QAnon, rather than people who tell Grok that Q is real: